Pitting corrosion and rust: What are the causes and solutions?

While stainless steel is often regarded as "rust-free", pitting and rust can occur if it is improperly handled and cared for.

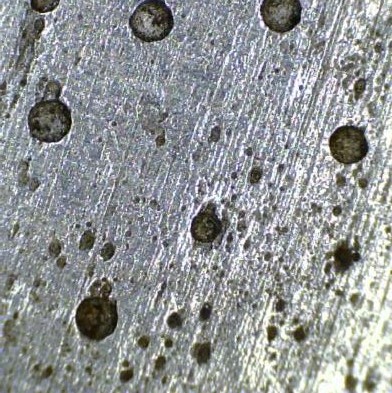

Pitting corrosion refers to small areas of corrosion that can appear as punctiform holes on the surface of stainless steels. In the depths of the material, the corrosion often expands significantly and remains unnoticed for a long time because of the low visibility on the surface.

Every stainless steel grade has a passive layer protection in the form of a thin oxide layer that protects against rust and corrosion. This layer is created through the reaction of oxygen with the chromium proportion in the stainless steel. However, the passive layer can be damaged by external influences and contamination. High chloride concentrations, which can often also be found in unsuspicious media such as well water, are particularly critical. Even very low and very high pH values can damage the passive layer of the stainless steel. To make sure that your medium does cause any corrosion, a laboratory analysis is advisable. Apart from that, regular and careful cleaning of your stainless steel tank is highly recommended. This helps to protect the passive layer within the tank and therefore contributes to a long-term rust- and corrosion-free life-cycle of the tank or reactor.

So-called flash rust can occur at outdoor installed tanks, especially when placed near to train tracks or busy roads. This can be caused by iron particles that are released when a train or car break is used. The iron particles eventually land on the stainless steel where the humidity in the air then causes surface corrosion, which is noticeable through small rusty dots. This form of corrosion is less critical than damage to the inner surface of a tank, but regular cleaning intervals are advisable to remove rust stains early on and thus maintain the corrosion resistance of the surface permanently.

Slight rusty discoloration can often be removed with simple household remedies such as a sponge and a little diluted detergent. The stainless steel must then be rinsed with clean water and later dried. If this does not lead to the desired goal, the process can be repeated with a suitable stainless steel cleaner (chloride-free). Pay attention to the instructions for use, as such cleaning agents should not take effect for too long.

If these derusting attempts have not been successful in removing the rust stains or if a certain amount of material layer has already been removed by corrosion, the surface can be mechanically treated. Before such repair works are initiated, a leak test (hydrostatic test) is advisable to assess if the damage can be repaired this way or if a leak has already occured. The mechanical treatment is based on grinding down the stainless steel surface until the traces of rust and corrosion pits are no longer visible, if the material thickness allows this work. It is then advisable to pickle and passivate the surface. Make absolutely sure that the tools for the mechanical processing of the stainless steel surface have not previously been used for the processing of conventional mild-steel, otherwise there is a risk of damaging the stainless steel with the residues of other steel grades.

Generally speaking, the vulnerability of stainless steel to corrosion differs greatly based on the exact type of alloy used to manufacture the tank. Stainless steels grades referred to as AISI 316 (e.g. 1.4404, 1.4571) are significantly more corrosion-resistant than the most common stainless steel type AISI 304 (1.4301). This is primarily due to an increased share of molybdenum inside the stainless steel, which stabilizes the passive layer and thus offers increased resistance to corrosion and rust. It is therefore advisable to research before the purchase decision of a stainless steel tank or reactor, if a higher-grade stainless steel is necessary for the future product to be used inside the tank.